by Avery Blankenship & Brice Lanham

While writing assessment can be a useful way to determine a student’s current experience with writing, it can be easy for assessment driven by pressures external to the classroom as well as heavy reliance on traditional grading systems to shift assessment away from the benefit of the student and towards the benefit of an institution.

The CCCC Committee on Assessment has a statement on writing assessment on their website. The general principles underlying their guidelines are as follows:

“Assessments of written literacy should be designed and evaluated by well-informed current or future teachers of the students being assessed, for purposes clearly understood by all the participants; should elicit from student writers a variety of pieces, preferably over a substantial period of time; should encourage and reinforce good teaching practices; and should be solidly grounded in the latest research on language learning as well as accepted best assessment practices.”

While these principles may seem obvious, assessing student writing can be difficult for a writing program to navigate when a student body can be made up of students from varying disciplines, personal backgrounds, and cultural touchstones.

Associated Legacy Records

2023-04-13T01:26:54Z

A

CoreFile

neu:m044tg16h

northeastern:drs:repository:staff

northeastern:drs:college_of_social_sciences_humanities:writing_program

public

000000000

neu:h989rv315

neu:h989rv315

000000000

000000000

/downloads/neu:m044tg182?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m044tg182?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m044tg182?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m044tg182?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m044tg182?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

/downloads/neu:m044tg182?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m044tg182?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m044tg182?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m044tg182?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m044tg182?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

PdfFile

PdfFile

neu:h989rv315

000000000

/downloads/neu:m044tg182?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m044tg182?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m044tg182?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m044tg182?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m044tg182?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

PdfFile

Basic Writing Skills Test for ENG 4100

Basic Writing Skills Test for ENG 4100

Basic Writing Skills Test for ENG 4100

Basic Writing Skills Test for ENG 4100

Blank writing skills exam

Evaluation

Evaluation

Evaluation

http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20326875

http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20326875

Evaluation

Basic Writing Skills Test for ENG 4100

Basic Writing Skills Test for ENG 4100

basic writing skills test for eng 004100

Basic Writing Skills Test for ENG 4100

Evaluation

info:fedora/afmodel:CoreFile

info:fedora/neu:h989rv315

2023-04-13T05:06:41.821Z

2023-04-13T01:29:12Z

A

CoreFile

neu:m044tg85x

northeastern:drs:repository:staff

northeastern:drs:college_of_social_sciences_humanities:writing_program

public

000000000

neu:h989rv315

neu:h989rv315

000000000

000000000

/downloads/neu:m044tg87g?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m044tg87g?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m044tg87g?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m044tg87g?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m044tg87g?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

/downloads/neu:m044tg87g?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m044tg87g?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m044tg87g?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m044tg87g?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m044tg87g?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

PdfFile

PdfFile

neu:h989rv315

000000000

/downloads/neu:m044tg87g?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m044tg87g?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m044tg87g?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m044tg87g?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m044tg87g?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

PdfFile

Packet of Readings for In-Class Entrance Assessment

Packet of Readings for In-Class Entrance Assessment

Packet of Readings for In-Class Entrance Assessment

Packet of Readings for In-Class Entrance Assessment

Packet of readings for students to read over

Guidelines

Guidelines

Evaluation

Guidelines

Evaluation

http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20326898

http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20326898

Guidelines

Evaluation

Packet of Readings for In-Class Entrance Assessment

Packet of Readings for In-Class Entrance Assessment

packet of readings for inclass entrance assessment

Packet of Readings for In-Class Entrance Assessment

Guidelines

Evaluation

info:fedora/afmodel:CoreFile

info:fedora/neu:h989rv315

2023-04-13T05:06:45.618Z

2023-04-13T01:30:14Z

A

CoreFile

neu:m044th099

northeastern:drs:repository:staff

northeastern:drs:college_of_social_sciences_humanities:writing_program

public

000000000

neu:h989rv315

neu:h989rv315

000000000

000000000

/downloads/neu:m044th11b?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m044th11b?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m044th11b?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m044th11b?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m044th11b?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

/downloads/neu:m044th11b?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m044th11b?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m044th11b?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m044th11b?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m044th11b?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

PdfFile

PdfFile

neu:h989rv315

000000000

/downloads/neu:m044th11b?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m044th11b?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m044th11b?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m044th11b?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m044th11b?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

PdfFile

Scoring Guide for Essay Descibing a Place

Scoring Guide for Essay Descibing a Place

Scoring Guide for Essay Descibing a Place

Scoring Guide for Essay Descibing a Place

Guidelines for grading student writing possibly from 80s-70s

Guidelines

Guidelines

Guidelines

http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20326906

http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20326906

Guidelines

Scoring Guide for Essay Descibing a Place

Scoring Guide for Essay Descibing a Place

scoring guide for essay descibing a place

Scoring Guide for Essay Descibing a Place

Guidelines

info:fedora/afmodel:CoreFile

info:fedora/neu:h989rv315

2023-04-13T05:07:24.541Z

2023-04-13T01:32:54Z

A

CoreFile

neu:m044th42b

northeastern:drs:repository:staff

northeastern:drs:college_of_social_sciences_humanities:writing_program

public

000000000

neu:h989rv315

neu:h989rv315

000000000

000000000

/downloads/neu:m044th44w?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m044th44w?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m044th44w?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m044th44w?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m044th44w?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

/downloads/neu:m044th44w?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m044th44w?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m044th44w?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m044th44w?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m044th44w?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

PdfFile

PdfFile

neu:h989rv315

000000000

/downloads/neu:m044th44w?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m044th44w?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m044th44w?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m044th44w?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m044th44w?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

PdfFile

English Writing Sample

English Writing Sample

English Writing Sample

English Writing Sample

Guidelines for submitting writing samples to test out of intro english courses

Guidelines

Guidelines

Evaluation

Guidelines

Evaluation

http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20326917

http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20326917

Guidelines

Evaluation

English Writing Sample

English Writing Sample

english writing sample

English Writing Sample

Guidelines

Evaluation

info:fedora/afmodel:CoreFile

info:fedora/neu:h989rv315

2023-04-13T05:07:28.231Z

2023-04-13T01:34:06Z

A

CoreFile

neu:m044th722

northeastern:drs:repository:staff

northeastern:drs:college_of_social_sciences_humanities:writing_program

public

000000000

neu:h989rv315

neu:h989rv315

000000000

000000000

/downloads/neu:m044th74m?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m044th74m?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m044th74m?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m044th74m?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m044th74m?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

/downloads/neu:m044th74m?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m044th74m?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m044th74m?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m044th74m?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m044th74m?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

PdfFile

PdfFile

neu:h989rv315

000000000

/downloads/neu:m044th74m?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m044th74m?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m044th74m?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m044th74m?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m044th74m?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

PdfFile

First Day Assessment Procedures

First Day Assessment Procedures

First Day Assessment Procedures

First Day Assessment Procedures

Instructions for the first day assessment procedures

Memo

Memo

Guidelines

Memo

Guidelines

http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20326927

http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20326927

Memo

Guidelines

First Day Assessment Procedures

First Day Assessment Procedures

first day assessment procedures

First Day Assessment Procedures

Memo

Guidelines

info:fedora/afmodel:CoreFile

info:fedora/neu:h989rv315

2023-04-13T05:07:41.997Z

2023-04-13T01:34:56Z

A

CoreFile

neu:m044tk04b

northeastern:drs:repository:staff

northeastern:drs:college_of_social_sciences_humanities:writing_program

public

000000000

neu:h989rv315

neu:h989rv315

000000000

000000000

/downloads/neu:m044tk06w?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m044tk06w?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m044tk06w?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m044tk06w?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m044tk06w?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

/downloads/neu:m044tk06w?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m044tk06w?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m044tk06w?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m044tk06w?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m044tk06w?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

PdfFile

PdfFile

neu:h989rv315

000000000

/downloads/neu:m044tk06w?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m044tk06w?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m044tk06w?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m044tk06w?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m044tk06w?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

PdfFile

Handbook

Handbook

Handbook

Handbook

Writing program handbook

Webpage

Webpage

Guidelines

Webpage

Guidelines

http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20326971

http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20326971

Webpage

Guidelines

Handbook

Handbook

handbook

Handbook

Webpage

Guidelines

info:fedora/afmodel:CoreFile

info:fedora/neu:h989rv315

2023-04-13T05:07:45.917Z

In a 2017 New York Times article entitled “Why Kids Can’t Write,” author Dana Goldstein writes that

“Three-quarters of both 12th and 8th graders lack proficiency in writing, according to the most recent National Assessment of Educational Progress. And 40 percent of those who took the ACT writing exam in the high school class of 2016 lacked the reading and writing skills necessary to complete successfully a college-level English composition class, according to the company’s data.”

Determining how to successfully assess student writing in a way that ultimately benefits the student can be tricky. By turning to some key documents from the Northeastern University Writing Program (See Excerpts below), we can see how writing assessment standards are constantly changing, and often very messy.

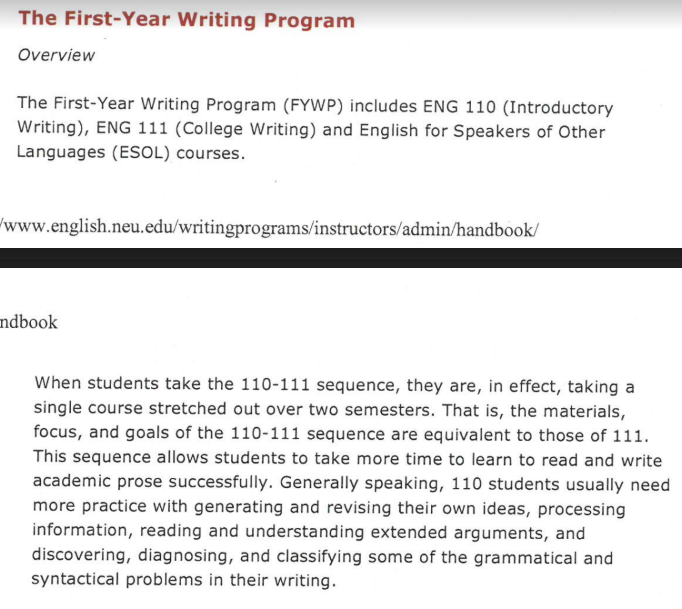

Excerpt 1: Writing Program Handbook (2006)

Some of the points of interest in this excerpt from the 2006 Writing Program Handbook, are the phrases used to describe introductory writing classes. When students are placed in the ENG 110-111 sequence, it is because they need time to “learn to read and write academic prose successfully” and they need more practice “processing information” and “reading and understanding extended arguments.” This prescriptive language describing the skill of college-level writers already sets students into categories of “good” or “bad” writers. Rather than describe students in the 110 track as perhaps not as experienced with academic writing as students who are taking ENG 111, the description of 110 and the desired outcomes place all emphasis on academic writing as the gateway to being able to understand the process of revision, written arguments, and generating ideas.

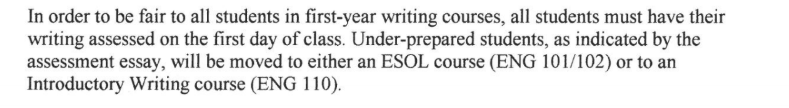

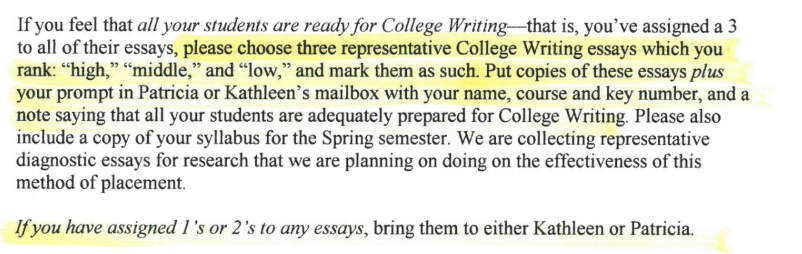

Excerpts 2-4: First Day Memo (2006)

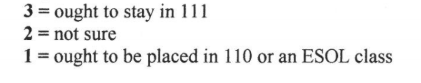

These excerpts from a 2006 memo to first-year writing instructors states that in order to be “fair” to all first-year writing students, they must be assessed on the first day of class to determine if their placement is accurate. Once the students are finished writing, the instructor is meant to assign a numerical grade (1, 2, or 3) to the essays. However, even in a situation where an instructor has determined that all of the essays produced have earned a 3, they must then pick three essays (one ranked “high,” “middle,” and “low”) from the group. As CCCC recommends in regards to placement, “if scoring systems are used, scores should derive from criteria that grow out of the work of the courses into which students are being placed.”

However, the grades being assigned to these placement essays are as follows:

Additionally, there is little mention of the role that the student plays in their own assessment.

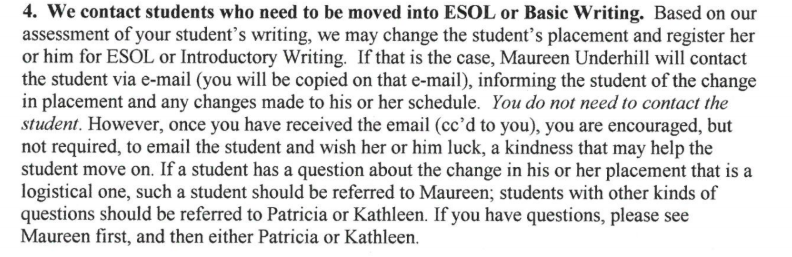

As CCCC recommends, “students should have the right to weigh in on their assessment. Self-placement without direction may become merely a right to fail, whereas directed self-placement, either alone or in combination with other methods, provides not only useful information but also involves and invests the student in making effective life decisions.” However as the memo later mentions, if a student is determined to require a change in placement after the first day writing assessment, they are merely contacted to inform them of their changed schedule. The instructor is not required to contact the student, at all, but only encouraged to send them some form of kindness that “may help the student move on.”

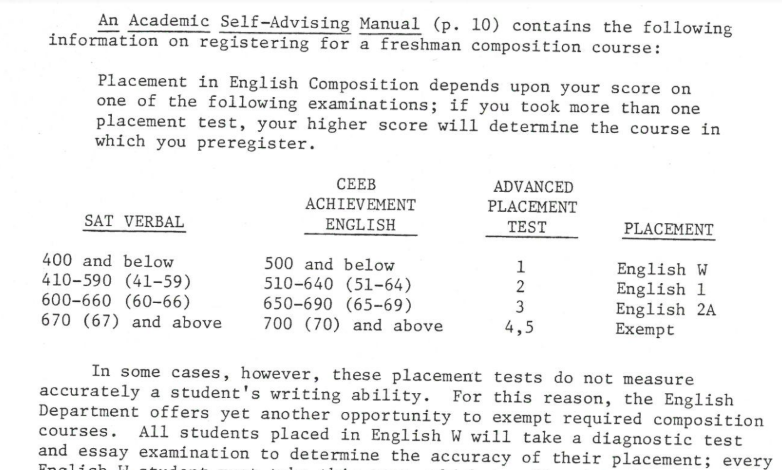

However, looking at documents that we date back to the 90s (right), we can see how much the process of writing assessment had changed by 2006.

In this document, we can see that students were placed into writing courses based on a combination of their SAT Verbal score, CEEB Achievement score, and Advanced Placement Test score. Although the document states that students who appear to be placed incorrectly can have their placement modified, this modification is through yet another exam. The emphasis on standardized tests only accounts for students who are good test-takers and doesn’t basis a judgment of student writing on any other environment where a student may excel as a writer.

Takeaways

This analysis is not intended to only point out places where the Northeastern Writing Program could have improved, but to show that writing assessment is a necessary but complicated problem. While students should have some role in their assessment, if too much control is given to the student, then that control could come as the cost of actual improvement in their writing. Additionally, it can be difficult to navigate how to refer to less experienced writers in program documentation.

As these documents have shown, language to describe the abilities of students is constantly evolving and strategies for determining how to assess writing experience is not a simple task for a writing program to handle.

This is an analysis (2020) of legacy records from the first two years of NUWPArc's development.

What are Legacy records?

The records associated with this exhibit come from NUWPArc's Legacy records collection. Records in this collection represent the early organization, selection, digitization, and classification procedures (tagging, metadata) that were applied to the first 100 documents our team ingested to the DRS.

The Legacy records collection showcases evolution of our project and processes from its first years (2018-2020). The system of tagging and metadata for records in this collection differ from the system used throughout the rest of the collection today. Learn more about how our processes have changed since these records were created.